Boltzmann learning of biological models

In this section, we describe the theoretical framework behind the DCA models.

Structure of the model and Boltzmann learning

DCA models bmDCA are probabilistic generative models that infer a probability distribution over sequence space. Their objective is to assign high probability values to sequences that are statistically similar to the natural sequences used to train the architecture while assigning low probabilities to those that significantly diverge. The input dataset is a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA), where each sequence is represented as a \(L\)-dimensional categorical vector \(\pmb a = (a_1, \dots, a_L)\) with \(a_i \in \{1, \dots, q\}\), each number representing one of the possible amino acids or nucleotides, or the alignment gap. To simplify the exposition, from here on, we will assume them to be amino acids. The following equation then gives the DCA probability distribution:

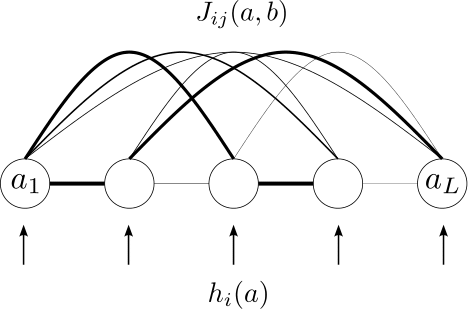

In this expression, \(Z\) is the normalization constant and \(E\) is the DCA energy function. The interaction graph \(\mathcal{G}=(\mathcal{V},\mathcal{E})\) is represented in a one-hot encoding format: the vertices \(\mathcal{V}\) of the graph are the \(L\times q\) combinations of all possible symbols on all possible sites, labeled by \({(i,a) \in \{1,\cdots,L\}\times \{1,\cdots,q\}}\), and the edges \(\mathcal{E}\) connect two vertices \((i,a)\) and \((j,b)\). The bias (or field) \(h_i(a)\) corresponding to the amino acid \(a\) on the site \(i\) is activated by the Kronecker \(\delta_{a_i,a}\) if and only if \(a_i=a\), and it encodes the conservation signal of the MSA. The coupling matrix \(J_{ij}(a, b)\) represents the coevolution (or epistatic) signal between pairs of amino acids at different sites, and is activated by the \(\delta_{a_i,a} \delta_{a_j,b}\) term if \(a_i=a\) and \(a_j=b\). Note that \(J_{ii}(a,b)=0\) for all \(a,b\) to avoid a redundancy with the \(h_i(a)\) terms, and that \(J_{ij}(a,b)=J_{ji}(b,a)\) is imposed by the symmetry structure of the model. The interaction graph \(\mathcal{G}\) can be chosen fully connected as in the bmDCA model, or it can be a sparse graph as in eaDCA and edDCA.

Scheme of the fully-connected DCA model (bmDCA)

Training the model

The training consists of adjusting the biases, the coupling matrix, and the interaction graph to maximize the log-likelihood of the model for a given MSA, which can be written as

where \(w^{(m)}\) is the weight of the data sequence \(m\), with \(\sum_{m=1}^M w^{(m)} =M_{\rm eff}\), and

are the empirical single-site and two-site frequencies computed from the data. Roughly speaking, \(f_i(a)\) tells us what is the empirical probability of finding the amino acid \(a\) in the position \(i\) of the sequence, whereas \(f_{ij}(a,b)\) tells us how likely it is to find together in a sequence of the data the amino acids \(a\) and \(b\) at positions respectively \(i\) and \(j\).

For a fixed graph \(\mathcal{G}\), we can maximize the log-likelihood by iteratively updating the parameters of the model in the direction of the gradient of the log-likelihood. By differentiating the log-likelihood (2), we find the update rule for the Boltzmann learning:

where \(p_i(a) = \langle \delta_{a_i,a}\rangle\), \(p_{ij}(a, b)=\langle \delta_{a_i,a}\delta_{a_j,b}\rangle\) are the one-site and two-site marginals of the model (1) and \(\gamma\) is a small rescaling parameter called learning rate. Notice that the convergence of the algorithm is reached when \(p_i(a) = f_i(a)\) and \(p_{ij}(a,b) = f_{ij}(a, b)\).

Monte Carlo estimation of the gradient

The difficult part of the algorithm consists of estimating \(p_i(a)\) and \(p_{ij}(a,b)\), because computing the normalization \(Z\) of Eq. (1) is computationally intractable, preventing us from directly computing the probability of any sequence. To tackle this issue, we estimate the first two moments of the distribution through a Monte Carlo simulation. This consists of sampling a certain number of fairly independent sequences from the probability distribution (1) and using them to estimate \(p_i(a)\) and \(p_{ij}(a, b)\) at each learning epoch. There exist several equivalent strategies to deal with it. Samples from the model (1) can be obtained via Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations either at equilibrium or out-of-equilibrium, where we start from \(N_c\) configurations (we refer to them as chains), chosen uniformly at random, from the data or the last configurations of the previous learning epoch, and update them using Gibbs or Metropolis-Hastings sampling steps up to a certain number of MCMC sweeps.

It has been shown in [Muntoni et al., 2021] for Boltzmann machines and, in general, for energy-based models [Decelle et al., 2021] that under certain conditions, training the model estimating the marginals from an out-of-equilibrium sampling leads to good enough generative models. Depending on the training set, these models can even be fairly close to what is achieved with perfectly equilibrated training.

For this reason, in adabmDCA 2.0, we implement a persistent contrastive divergence (PCD) scheme, in which the computation of the gradient is done with chains that may be slightly out of equilibrium.

In particular, chains are persistent, i.e. they are initialized at each learning epoch using the last sampled configurations of the previous epoch. This is done because sampling from configurations that are already close to the stationary state of the model at the current training epoch is much more convenient. Furthermore, the number of sweeps to be performed should be large enough to ensure that the updated chains are close enough to an equilibrium sample of the probability (1). In practice, this is done by fixing the number of sweeps to a convenient value, \(k\), that trades off between a reasonable training time and a fair mixing of the chains.

Convergence criterium

To decide when to terminate the training, we monitor the two-site connected correlation functions of the data and of the model, which are defined as

When the Pearson correlation coefficient between the two reaches a target value, set by default at 0.95, the training stops.

Once the model is trained, we can generate new sequences by sampling from the probability distribution (1), infer contacts on the tertiary structure by analyzing the coupling matrix, or propose and assess mutations through the DCA energy function \(E\).

Training sparse models

What we have described so far is true for all the DCA models considered in this work, but we have not yet discussed how to adjust the topology of the interaction graph \(\mathcal{G}\). In the most basic implementation, bmDCA, the graph is assumed to be fully connected (every amino acid of any residue is connected with all the rest) and the learning will only tweak the strength of the connections. This results in a coupling matrix with \(L (L - 1) q^2 / 2\) independent parameters, where \(q = 21\) for amino acid and \(q=5\) for nucleotide sequences. However, it is well known from the literature that the interaction network of protein families tends to be relatively sparse, suggesting that only a few connections should be necessary for reproducing the statistics of biological sequence data. This observation brings us to devising a training routine that produces a DCA model capable of reproducing the one and two-body statistics of the data with a minimal amount of couplings.

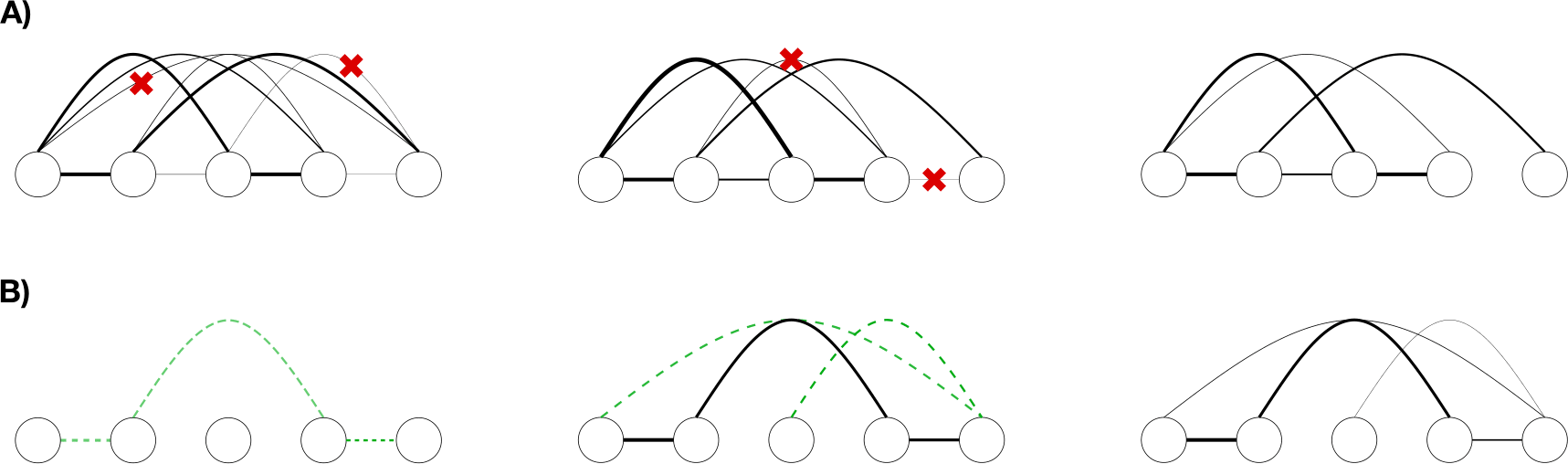

To achieve this, we implemented two different routines: eaDCA which promotes initially inactive parameters to active coupling starting from a profile model, and edDCA, which iteratively prunes active but negligible parameters starting from a dense fully-connected DCA model.

Element activation DCA

In eaDCA (figure sparse models-B), we start from an empty interaction graph \(\mathcal{E} = \oslash\), meaning that no connection is present. Each training step is divided into two different moments: first, we update the graph, and then we bring the model to convergence once the graph is fixed (a similar pipeline has been proposed in [Calvanese et al., 2024]).

To update the graph, we first estimate \(p_{ij}(a, b)\) for the current model and, from all the possible quadruplets of indices \((i, j, a, b)\), we select a fixed number \texttt{nactivate} of them as being the ones for which \(p_{ij}(a, b)\) is “the most distant” from the target statistics \(f_{ij}(a,b)\). We then activate the couplings corresponding to those quadruplets, obtaining a new graph \(\mathcal{E}'' \supseteq \mathcal{E}\). Notice that the number of couplings that we add may change, because some of the selected ones might be already active.

Element decimation DCA

In edDCA (Figure sparse models-A), we start from a previously trained bmDCA model and its fully connected graph \(\mathcal{G}\). We then apply the decimation algorithm, in which we prune connections from the edges \(\mathcal{E}\) until a target density of the graph is reached, where the density is defined as the ratio between the number of active couplings and the number of couplings of the fully connected model. Similarly to eaDCA, each iteration consists of two separate moments: graph updating and activate parameter updating.

To update the graph, we remove the fraction drate of active couplings that, once removed, produce the smallest perturbation on the probability distribution at the current epoch. In particular, for each active coupling, one computes the symmetric Kullback-Leibler distances between the current model and a perturbed one, without that target element. One then removes the drate elements which exhibit the smallest distances (see [Barrat-Charlaix et al., 2021] for further details).

Parameter updates in between decimations/activations

In both procedures, to bring the model to convergence on the graph, we perform a certain number of parameter updates in between each step of edge activation or decimation, using the update rule (4). Between two subsequent parameter updates, \(k\) sweeps are performed to update the Markov chains.

In the case of element activation we perform a

fixed number of parameter updates,

specified by the input parameter gsteps.

Instead, when pruning the graph, we keep updating the parameters with the rule (4) until the Pearson correlation coefficient reaches a target value.

Schematic representation of the sparse model training. A) edDCA, the sparsification is obtained by progressively pruning contacts from an initial fully connected model. B) eaDCA, the couplings are progressively added during the training.